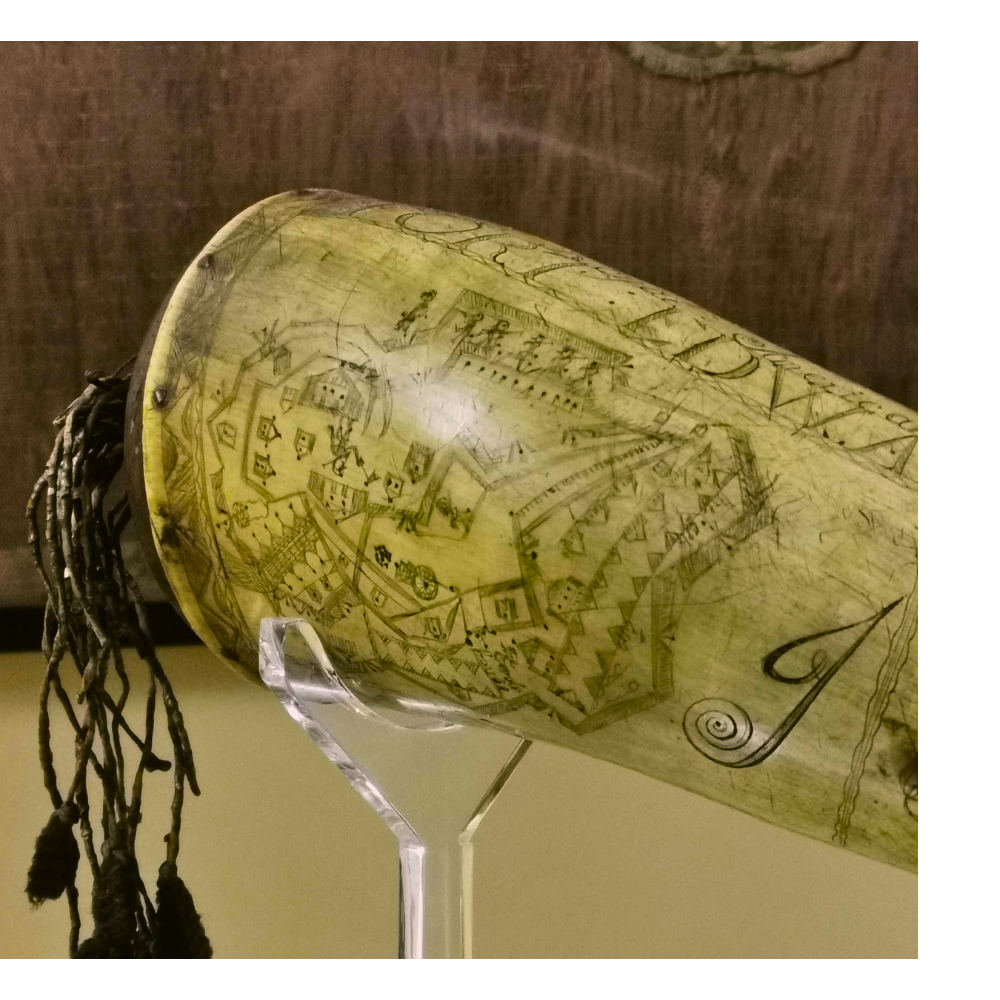

A powderhorn carved with a map of Fort Edward, dated 1757 and the initials of its owner, John Longsdon.

This powder horn is among the oldest and most evocative objects on display in the Museum. It once belonged to Lieutenant John Longsdon of the 62nd (Royal American) Regiment, later redesignated the 60th Regiment. Records about Longsdon are scarce: he was appointed Senior Lieutenant on 7 January 1756, but by 1759 his name had disappeared from the Army List, suggesting a brief military career.

The horn itself, carved in 1757, is both functional and artistic. Its surface depicts the layout of Fort Edward in present-day New York State, while its strap is crafted from porcupine quills.

Fort Edward occupied a site long known as the “great carrying place,” a strategic portage between the Hudson River and Lake Champlain. This corridor formed the most direct inland route between New York City and the St. Lawrence River, vital for travel and trade since the 17th century. In 1755, General Phineas Lyman began constructing a fort there under the orders of Sir William Johnson. Originally named Fort Lyman, it was soon renamed Fort Edward in honour of Edward Augustus, Duke of York and Albany. Built in the Vauban style, the fort boasted three bastions and was protected by a dry moat fourteen feet wide and eight feet deep.

For soldiers like Longsdon, a powder horn was indispensable. Gunpowder was highly volatile, and metal containers risked igniting from a stray spark. Horns offered a safer alternative: naturally hollow, waterproof, and non-metallic, they kept powder dry and secure. Their design was practical, too: the wide end allowed easy refilling, while the narrow tip ensured careful dispensing. When polished, horn became semi-translucent, letting a soldier quickly judge how much powder remained inside.

This powder horn is not only a testament to 18th-century craftsmanship but also a tangible link to the early years of the Royal American Regiment and the contested landscapes of colonial North America.